IELTS Materials and Resources, Get IELTS Tips, Tricks & Practice Test |

- Bark Is Worse Than One’s Bite – Idiom Of The Day For IELTS

- 2017 IELTS Speaking Part 1 Topic: Job/Work & Sample Answers

- Nascent – Word Of The Day For IELTS

- IELTS READING PRACTICE TEST 32 WITH ANSWERS

- IELTS Writing Practice Test 33 (Task 1 & 2) & Sample Answers

- Two-Word Prepositions to Score Band 7.0+ in IELTS Writing & Speaking (Part 3)

- IELTS Reading Recent Actual Test 10 in 2016 with Answer Key

| Bark Is Worse Than One’s Bite – Idiom Of The Day For IELTS Posted: 08 Jan 2017 08:45 AM PST Bark Is Worse Than One’s Bite – Idiom Of The Day For IELTS Speaking.Definition: Sounding more frightening than you actually are. Example: “Though our neighbour is forever shouting at us, Larry says his bark is worse than his bite“ “I wouldn’t be scared of her if I were you. Her bark is worse than her bite.” “The boss seems mean, but his bark is worse than his bite.“ Exercise:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2017 IELTS Speaking Part 1 Topic: Job/Work & Sample Answers Posted: 08 Jan 2017 05:04 AM PST Job/ WorkWhat do you do? What are your responsibilities? Why do you choose this job? Is there some other kind of work you would rather do? Describe the company or organization you work for. Do you enjoy your work? What do you like/dislike about your job? (Possibly)Do you miss being a student? What are the advantages of having your own business rather than working for someone else? What do you see yourself doing in the next 10 years?

Sample Answers:1.What do you do? For the past few months I've been working for The Guardian as a news editor. In fact this is my first job ever, I'm working really hard to contribute to the success of this prestigious newspaper. 2. What are your responsibilities? As a part-time editor, I am responsible for editing news related to different current affairs as well as collecting information for the newspaper edition. 3. Why did you choose to do that type of work (or, that job)? I guess it's mainly because of the job flexibility & my passion for journalism. To be more specific, this job offers me alternatives to the typical nine-to-five work schedule, enabling me to find a better balance between work and life. Besides, this job gives me opportunities to pursue my dream to become a journalist down the road. Vocabulary Job flexibility (expression) gives employees flexibility on how long, where and when they work. Nine-to-five work (phrase) the normal work schedule for most jobs 4. Is there some other kind of work you would rather do? At present I don't think I'm able to dedicate myself to any other job rather than this one. In fact, to me it's the experiences and opportunities I can gain that really matters. Vocabulary To dedicate to Sth (v) devote (time or effort) to a particular task or purpose 5. Describe the company or organization you work for. The Guardian is a National British daily newspaper which offers free access both to current news and an archive of three million stories. In April 2011, MediaWeek reported that The Guardian was the fifth most popular newspaper site in the world. I personally believe that the guardian is the inspirational workplace for all people who dream of becoming a journalist. 6. Do you enjoy your work? Most of the time. Contributing to the news production for a world-class newspaper gives me a sense of satisfaction and pride. Vocabulary World-class (adj) of or among the best in the world 7. What do you like/dislike about your job? Well the perk of being a news editor is that you'll surround yourself with inspiring news on a daily basis. What I don't like about this job is that I have to do a thousand edits to get the final one to meet the requirement of my boss. Sometimes I feel a bit overloaded with tons of tasks. Vocabulary Perk (n) an advantage or something extra that you are given because of your job Overloaded (adj) to give excessive work, responsibility, or information to 9. (Possibly)Do you miss being a student? I surely will miss my student life once I get involve in the workplace. For me I think when I'm a student, at least I have someone guide me, whereas at work mostly you must guide yourself. The academic environment appears to be a comfort zone for me, while I'm sure I'll struggle with fitting in the working environment. Vocabulary To get involve in (v) to become a part of (an organization) To fit in (v) to become suitable or appropriate for Sth or SO | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nascent – Word Of The Day For IELTS Posted: 08 Jan 2017 03:02 AM PST Nascent – Word Of The Day For IELTS Speaking And WritingNascent /ˈnæsənt/ (Adjective) Meaning:(formal) coming into existence or starting to develop Synonyms:Growing, Fledgling, Burgeoning Collocations:

Examples:

Exercises:Try to use this word “nascent” in your speech Describe a new invention that impressed you a lot You should say:

Sample Answer: Today I will talk with you about a new invention that extremely astonished me. I read a related article while I was surfing the Internet. It was about a ring called Nimb which was designed to be a quick, subtle way to send your location to anyone from friends to emergency personnel to alert them that you’re in a dangerous situation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IELTS READING PRACTICE TEST 32 WITH ANSWERS Posted: 07 Jan 2017 11:45 PM PST Section 1You should spend How to run a… Publisher and author David Harvey on what makes a good management book. A Prior to the Second World War, all the management books ever written could be comfortably stacked on a couple of shelves. Today, you would need a sizeable library, with plenty of room for expansion, to house them. The last few decades have seen the stream of new titles swell into a flood. In 1975, 771 business books were published. By 2000, the total for the year had risen to 3,203, and the trend continues. B The growth in pubishing activity has followed the rise and rise of management to the point where it constitutes a mini-industry in its own right. In the USA alone, the book market is worth over $lbn. Management consultancies, professional bodies and business schools were part of this new phenomenon, all sharing at least one common need: to get into print. Nor were they the only aspiring authors. Inside stories by and about business leaders balanced the more straight-laced textbooks by academics. How-to books by practising managers and business writers appeared on everything from making a presentation to developing a business strategy. With this upsurge in output, it is not really surprising that the quality is uneven. C Few people are probably in a better position to evaluate the management canon than Carol Kennedy, a business journalist and author of Guide to the Management Gurus, an overview of the world's most influential management thinkers and their works. She is also the books editor of The Director. Of course, it is normally the best of the bunch that are reviewed in the pages of The Director. But from time to time, Kennedy is moved to use The Director’s precious column inches to warn readers off certain books. Her recent review of The Leader's Edge summed up her irritation with authors who over-promise and under-deliver. The banality of the treatment of core competencies for leaders, including the ‘competency of paying attention', was a conceit too far in the context of a leaden text. 'Somewhere in this book,' she wrote,'there may be an idea worth reading and taking note of, but my own competency of paying attention ran out on page 31.' Her opinion of a good proportion of the other books that never make it to the review pages is even more terse.'Unreadable' is her verdict. D Simon Caulkin, contributing editor of the Observer’s management page and former editor of Management Today, has formed a similar opinion. A lot is pretty depressing, unimpressive stuff.' Caulkin is philosophical about the inevitability of finding so much dross. Business books, he says,'range from total drivel to the ambitious stuff. Although the confusing thing is that the really ambitious stuff can sometimes be drivel.' Which leaves the question open as to why the subject of management is such a literary wasteland. There are some possible explanations. E Despite the attempts of Frederick Taylor, the early twentieth-century founder of scientific management, to establish a solid, rule-based foundation for the practice, management has come to be seen as just as much an art as a science. Once psychologists like Abraham Maslow, behaviouralists and social anthropologists persuaded business to look at management from a human perspective, the topic became more multidimensional and complex. Add to that the requirement for management to reflect the changing demands of the times, the impact of information technology and other factors, and it is easy to understand why management is in a permanent state of confusion. There is a constant requirement for reinterpretation, innovation and creative thinking: Caulkin's ambitious stuff. For their part, publishers continue to dream about finding the next big management idea, a topic given an airing in Kennedy's book. The Next Big Idea. F Indirectly, it tracks one of the phenomena of the past 20 years or so: the management blockbusters which work wonders for publishers' profits and transform authors’ careers. Peters and Waterman's In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies achieved spectacular success. So did Michael Hammer and James Champy’s book. Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution. Yet the early euphoria with which such books are greeted tends to wear off as the basis for the claims starts to look less than solid. In the case of In Search of Excellence, it was the rapid reversal of fortunes that turned several of the exemplar companies into basket cases. For Hammer's and Champy's readers, disillusion dawned with the realisation that their slash-and-burn prescription for reviving corporate fortunes caused more problems than it solved. G Yet one of the virtues of these books is that they could be understood.There is a whole class of management texts that fail this basic test.'Some management books are stuffed with jargon,’ says Kennedy.'Consultants are among the worst offenders.' She believes there is a simple reason for this flight from plain English.’They all use this jargon because they can'c think clearly. It disguises the paucity of thought.’ H By contrast, the management thinkers who have stood the test of time articulate their ideas in plain English. Peter Drucker, widely regarded as the doyen of management thinkers, has written a steady stream of influential books over half a century. 'Drucker writes beautiful, dear prose.' says Kennedy, 'and his thoughts come through.' He is among the handful of writers whose work, she believes, transcends the specific interests of the management community. Caulkin also agrees that Drucker reaches out to a wider readership. ‘What you get is a sense of the larger cultural background,' he says.'That's what you miss in so much management writing.' Charles Handy, perhaps the most successful UK business writer to command an international audience, is another rare example of a writer with a message for the wider world. Questions 1—2 Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D. Write your answers in boxes 1 and 2 on your answer sheet. 1 What does the writer say about the increase in the number of management books published? A It took the publishing industry by surprise. B It is likely to continue. C It has produced more profit than other areas of publishing. D It could have been foreseen. 2 What does the writer say about the genre of management books? A It includes some books that cover topics of little relevance to anyone. B It contains a greater proportion of practical than theoretical books. C All sorts of people have felt that they should be represented in it. D The best books in the genre are written by business people. Questions 3-7 Reading Passage 1 has eight paragraphs A-H. Which paragraph contains the following information! Write the correct letter A-H in boxes 3-7 on your answer sheet. 3 reasons for the deserved success of some books 4 reasons why managers feel the need for advice 5 a belief that management books are highly likely to be very poor 6 a reference to books nor considered worth reviewing 7 an example of a group of people who write particularly poor books Questions 8-13 Look at the statements (Questions 8-13) and the list of books below. Match each statement with the book it relates to. Write the correct letter A-E in boxes 8-13 on your answer sheet. NB You may use any letter more than once. 8 It examines the success of books in the genre. 9 Statements made in it were later proved incorrect. 10 It tails to live up to claims made about it. 11 Advice given in it is seen to be actually harmful. 12 It examines the theories of those who have developed management thinkin 13 It states die obvious in an unappealing way.

Section 2You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on Reading Passage 2. Reading Passage 2 has five paragraphs A-E. Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list oj headings below. Write the correct number i—x in boxes 14—18 on your answer sheet.

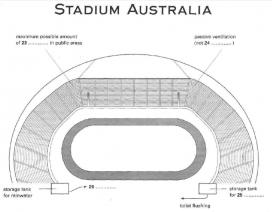

14 Paragraph A 15 Paragraph B 16 Paragraph C 17 Paragraph D 18 Paragraph E Stadium Australia A You might ask, why be concerned about the architecture of a stadium? Surely, as Long as die action is entertaining and the building is safe and reasonably comfortable, why should the aesthetics matter' This one question has dominated my professional life, and its answer is one 1 find myself continually rehearsing. If one accepts that sporting endeavour is as important an outlet for human expression as, say, the theatre or cinema, fine art or music, why shouldn't the buildings in which we celebrate this outlet he as grand and as inspirational as those we would expect, and demand, in those other areas of cultural life? Indeed, one could argue that because stadiums are, in many instances, far more popular than theatres or art galleries, we should actually devote more, and nor less, attention to their form. Stadiums have frequently been referred to as 'cathedrals'. Football has often been dubbed 'the opera of the people'. What better way, therefore, to raise the general public's awareness and appreciation of quality design than to offer them the very’ best buildings in the one area of life that seems to touch them most? Could it even be drat better stadiums might just make tor better citizens? B But then maybe, as my detractors have labelled me in the past, 1 am a snob. Maybe I should just accept that sport, and its associated accoutrements and products, is an essentially tacky and ephemeral business, while stadium design is all too often driven by pragmatists and penny-pinchers. Certainly, when 1 first started writing about stadium architecture, one of the first and most uncomfortable truths 1 had to confront was that some of the mast popular stadiums in the world were also amongst the the least attractive or innovative in architectural terms. 'Worthy and predictable' has usually won more votes than 'daring and different'. Old Trafford football ground in Manchester, the Yankee Stadium in New York, Ellis Park in Johannesburg. The list is long and is not intended to suggest that these are necessarily poor buildings. Rather, that each has derived its reputation more from the events that it has staged, from its associations, than from the actual form it takes. Equally, those stadiums whose forms have been revered – such as the Maracana in Rio, oi the San Siro in Milan – have turned out to be rather poorly designed in several respects, once one analyses them not as icons but as functioning 'public assembly facilities' (to use the current jargon). Finding the balance between beauty and practicality has never been easy. C Homebush Bay was the site of rhe main Olympic Games complex for the Sydney Olympics of 2000. To put it politely, 1 am no great admirer of the Olympics as an event, or, rather, of the insane pressures its past bidding procedures have placed upon candidate cities. Nor, as a spectator, do 1 much enjoy the bloated Games programme and the consequent demands this places upon the designers of stadiums. Yet in my calmer moments ir would be churlish to deny that, if approached sensibly and imaginatively, the opportunity to stage the Games can yield enormous benefits in the long term (as well they should, considering the expenditure involved), if not (or sport then at least for the cause of urban regeneration. Following in Barcelona's footsteps, Sydney undoubtedly set about its urban regeneration in a wholly impressive way. To an outsider, the 760-hectare sire at Homebush Bay, once the home of an abattoir, a racecourse, a brickworks and light industrial units, seemed miles from anywhere – it was actually fifteen kilometres from the centre of Sydney and pretty much in the heart of the city's extensive conurbation. Some £1.3 billion worth of construction and reclamation was commissioned, all of it, crucially, with an eye to post- Olympic usage- Strict guidelines, studiously monitore by Greenpeace, ensured that the 2000 Games would be the most environmentally friendly ever. What's more, much of the work was good-looking, distinctive and lively. 'That's a reflection of the Australian spirit,' I was told. D At the centre of Homebush lay the main venue for the Olympics, Stadium Australia. It was funded by means of a BOOT (Budd, Own, Operate and Transfer) contract, which meant that the Stadium Australia consortium, led by rhe contractors Multiplex and the financiers Hambros, bore i he bulk of the construction costs, in return for which it was allowed to operate the facility for thirty years, and thus, it hopes, recoup its outlay, before handing the whole building over to the New South Wales government in the year 2030. E Stadium Australia was the most environmentally friendly Olympic stadium ever built. Every single product and material used had to meet strict guidelines, even if it turned our to he more expensive. All the timber was either recycled or derived from renewable sources. In order to reduce energy’ costs, the design allowed for natural lighting in as many public areas as possible, supplemented by solar-powered units. Rainwater collected from the roof ran off into storage- ranks, where it could be tapped for pitch irrigation. Stormwater run-off was collected for toilet flushing. Wherever possible, passive ventilation was used instead of mechanical air- conditioning. Even the steel and concrete from the two end stands due to be demolished at the end of the Olympics was to be recycled. Furthermore, no private cars were allowed on the Homebush site. Instead, every spectator was to arrive by public transport, and quite right too. If ever there was a stadium to persuade a sceptic like myself that the Olympic Games do, after all, have a useful function in at least setting design and planning trends, this was the one. 1 was, and still am, I freely confess, quite knocked out by Stadium Australia. Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 19-22 on your answer sheet unite TRUE if the statement agrees with the information FALSE if the statement contradicts the information NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this 19 The public have been demanding a better quality of stadium design. 20 It is possible that stadium design has an effect on people's behaviour in life in general. 21 Some stadiums have come in for a lot more criticism than others. 22 Designers of previous Olympic stadiums could easily have produced far better designs. Question 23-26 Label the diagram below Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the reading passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.  You should spend about 20 minutes on question 27-40 which are base on Reading passage 3 A Theory of Shopping For a one-year period I attempted to conduct an ethnography of shopping on and around a street in North London. This was carried out in association with Alison Clarke. I say ‘attempted’ because, given the absence of community and the intensely private nature of London households, this could not be an ethnography in the conventional sense. Nevertheless, through conversation, being present in the home and accompanying householders during their shopping, I tried to reach an understanding of the nature of shopping through greater or lesser exposure to 76 households. My part of the ethnography concentrated upon shopping itself. Alison Clarke has since been working with the same households, but focusing upon other forms of provisioning such as the use of catalogues (see Clarke 1997). We generally first met these households together, but most of the material that is used within this particular essay derived from my own subsequent fieldwork. Following the completion of this essay, and a study of some related shopping centres, we hope to write a more general ethnography of provisioning. This will also examine other issues, such as the nature of community and the implications for retail and for the wider political economy. None of this, however, forms part of the present essay, which is primarily concerned with establishing the cosmological foundations of shopping. To state that a household has been included within the study is to gloss over a wide diversity of degrees of involvement. The minimum requirement is simply that a householder has agreed to be interviewed about their shopping, which would include the local shopping parade, shopping centres and supermarkets. At the other extreme are families that we have come to know well during the course of the year. Interaction would include formal interviews, and a less formal presence within their homes, usually with a cup of tea. It also meant accompanying them on one or several ‘events’, which might comprise shopping trips or participation in activities associated with the area of Clarke’s study, such as the meeting of a group supplying products for the home. In analysing and writing up the experience of an ethnography of shopping in North London, I am led in two opposed directions. The tradition of anthropological relativism leads to an emphasis upon difference, and there are many ways in which shopping can help us elucidate differences. For example, there are differences in the experience of shopping based on gender, age, ethnicity and class. There are also differences based on the various genres of shopping experience, from a mall to a corner shop. By contrast, there is the tradition of anthropological generalisation about ‘peoples’ and comparative theory. This leads to the question as to whether there are any fundamental aspects of shopping which suggest a robust normativity that comes through the research and is not entirely dissipated by relativism. In this essay I want to emphasize the latter approach and argue that if not all, then most acts of shopping on this street exhibit a normative form which needs to be addressed. In the later discussion of the discourse of shopping I will defend the possibility that such a heterogenous group of households could be fairly represented by a series of homogenous cultural practices. The theory that I will propose is certainly at odds with most of the literature on this topic. My premise, unlike that of most studies of consumption, whether they arise from economists, business studies or cultural studies, is that for most households in this street the act of shopping was hardly ever directed towards the person who was doing the shopping. Shopping is therefore not best understood as an individualistic or individualising act related to the subjectivity of the shopper. Rather, the act of buying goods is mainly directed at two forms of ‘otherness’. The first of these expresses a relationship between the shopper and a particular other individual such as a child or partner, either present in the household, desired or imagined. The second of these is a relationship to a more general goal which transcends any immediate utility and is best understood as cosmological in that it takes the form of neither subject nor object but of the values to which people wish to dedicate themselves. It never occurred to me at any stage when carrying out the ethnography that I should consider the topic of sacrifice as relevant to this research. In no sense then could the ethnography be regarded as a testing of the ideas presented here. The Literature that seemed most relevant in the initial anaLysis of the London material was that on thrift discussed in chapter 3. The crucial element in opening up the potential of sacrifice for understanding shopping came through reading Bataiile. Bataille, however, was merely the catalyst, since I will argue that it is the classic works on sacrifice and, in particular, the foundation to its modern study by Hubert and Mauss (1964) that has become the primary grounds for my interpretation. It is important, however, when reading the following account to note that when I use the word ‘sacrifice’, I only rarely refer to the colLoquial sense of the term as used in the concept of the ‘self-sacrificial’ housewife. Mostly the allusion is to this Literature on ancient sacrifice and the detailed analysis of the complex ritual sequence involved in traditional sacrifice. The metaphorical use of the term may have its place within the subsequent discussion but this is secondary to an argument at the level of structure. Questions 27-29 Choose THREE letters A-F. Write your answers in boxes 27-29 on your answer sheet. Which THREE of the folloivmg are problems the writer encountered when conducting his study? A uncertainty as to what the focus of the study should he B the difficulty of finding enough households to make the study worthwhile C the diverse nature of the population ot the area D the reluctance of people to share information about their personal habits E the fact that he was unable to study some people's habits as much as others F people dropping out of the study after initially agreeing to take part Questions 30-37 Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 30-37 on your answer sheet write YES if the statement agrees with the news of the writer NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this 30 Anthropological relativism is more widely applied than anthropological generalisation. 31 Shopping lends itself to analysis based on anthropological relativism. 32 Generalisations about shopping are possible. 33 Tire conclusions drawn from this study will confirm some of the findings of other research. 34 Shopping should be regarded as a basically unselfish activity. 35 People sometimes analyse their own motives when they are shopping. 36 The actual goods bought are the primary concern in the activity of shopping. 37 It was possible to predict the outcome of the study before embarking on it. Questions 38-40 Complete the sentences below with words taken from Reading Passage 3. Use NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS for each answer. Write your answer in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet. 38 The subject of written research the writer first thought was directly connected with his study was……………………………………….. 39 The research the writer has been most inspired by was carried out by……………………………. 40 The writer mostly does not use the meaning of 'sacrifice' that he regards as………………………. ANSWER KEY FOR IELTS READING PRACTICE TEST Question 1-2 1 Answer: B Note Paragraph A: The fact that you would need ‘plenty of room for expansion’ in your library of management books means that the increase will continue and many more books will be produced. Also, ‘the trend continues' – the increase is still happening. Option A {paragraph B) is incorrect. The number of management books has grown so much that it has created its own ‘mini-industry’, but the writer does not say that the growth surprised people in the industry. Option C (paragraph B) is incorrect. The writer says how much money is made from management books, but does not say that this figure is higher than the amount made from other kinds of book. Option D (paragraph A) is incorrect. The writer talks about the period during which the growth has happened, but does not say that it was possible in the past to predict that this growth would happen. 2 Answer: C Note Paragraph B: The writer lists all kinds of people who have produced management books. These people fell a ‘need to get into print’ or were ‘aspiring authors’, which means they wanted to write the books, rather than that someone else asked them to do so. Option A (paragraph B) is incorrect. The writer says that all sorts of books have been written and that 'the quality is uneven’ (some are better than others!, but does not say that the content of any of them is completely irrelevant. Option B (paragraph B) is incorrect. It’s likely that the books by business leaders are more practical and the books by academics more theoretical, but the writer does not say that there are more of one kind than another. Option D (paragraph B) is incorrect. The writer says that some books are better than others, but does not say which ones are better than others. Questions 3-7 3 Answer: H Note Drucker’s and Handy’s books are said to deserve their success because they are well-written, clear and relevant to a wide range of people. 4 Answer: E Note ‘Add to that …’. The writer lists here reasons why managers are ‘in a permanent state of confusion’ and need advice on management. 5 Answer: D Note We are told that Caulkin ‘is philosophical about the inevitability of finding so much dross’. He is not surprised that it is certain that most management books are rubbish. 6 Answer: C Note Last sentence: Some books never make it to the review pages’ Iare not considered worth reviewing) because they are ‘unreadable’. 7 Answer: G Note Kennedy says that consultants ‘are among the worst offenders’. They are a group of people who are particularly guilty of writing books full of jargon that cannot be understood. Questions 8-13 8 Answer: C Note Paragraph E, last sentence and paragraph F, 1″ sentence: This book is about publishers’ desire to find ‘the next big management idea’, which will result in very high book sales. It ‘tracks’ (examines the progress of) ‘blockbusters’ (books that have sold in enormous quantities) in the management genre over the past 20 years, making big profits for publishers and authors. The Next Big Idea therefore looks at management books that have been very successful. 9 Answer: D Note Paragraph F: This book made claims that ‘started to look less than solid’ (began to appear not to be based on fact) because some of the companies used in it as examples of good companies suffered a rapid ‘reversal of fortune’ (quickly changed from being successful to being unsuccessful) and became ‘basket cases’ (in a hopeless situation). 10 Answer: B Note Paragraph C: This book is said to ‘over-promise’ and ‘under-deliver’, which means that the writer of it makes claims about how good it is, but the book itself does not fulfil the promises made, and does not contain what it is said to contain. 11 Answer: E Note Paragraph F, last sentence: This book suggested a certain way of improving a company’s position, but people who followed this advice realised that it ’caused more problems than it solved’. 12 Answer: A Note Paragraph C, T’ sentence: This book provides an ‘overview’ (a general look) at people whose ideas and books have been the most influential. 13 Answer: B Note Paragraph C: There is a reference to the ‘banality’ (stating of things that are obvious and therefore not worth saying) of this book, and the fact that the writing is ‘leaden’ (very dull), with the result that Kennedy had completely lost Interest in it after 31 pages. READING Passage 2 Questions 14-18 14 Answer: viii Note The whole paragraph consists of the writer’s argument that the architecture of a stadium is important. Throughout the first paragraph, he gives reasons in support of his strongly held belief that the architecture of stadiums is just as important as the architecture of other buildings because sport itself Is important in people’s lives. 15 Answer: iv Note In most of this paragraph, the writer contrasts stadiums that are popular with stadiums that are considered attractive. The most popular stadiums are not, in his view, attractive ones, and the ones that are considered attractive are also said not to be very good from a practical point of view. 16 Answer: vi Note In this paragraph, the writer says that Sydney 'set about’ (started) its programme of urban regeneration ‘in a wholly impressive way’ when it was preparing to stage the Olympics. His main point in the paragraph is that, although he does not normally like the buildings produced for Olympic Games, staging the games can be good for ‘urban regeneration’, – in Sydney the work that was carried out at the beginning of the process of getting ready for the Games (listed in the 2nd half of the paragraph) was very good and suggested that the outcome would be a good one. 17 Answer: v Note This paragraph describes the special arrangement for the funding and ownership of Stadium Australia. That it was a special arrangement is indicated by the fact that it had a special name {‘BOOT’). 18 Answer: ii Note This paragraph mainly describes the ways in which various aspects of the stadium met the general requirement of being environmentally friendly. ► Questions 19-22 19 Answer: NOT GIVEN Note Paragraph A: ‘What better way The writer is saying that the public would be more aware of and appreciate ‘quality design’ if sports stadiums were examples of good design. His point throughout paragraph A is that people expect buildings in which cultural events take place to be grand’ and ‘inspirational’ (magnificent and exciting), and that stadiums should also be like that. However, he does not say whether or not the public complain about the quality of the design of stadiums. 20 Answer: TRUE Note Paragraph A, last sentence: The writer says that it’s possible that ‘better stadiums might make for’ (help to create) ‘better citizens’. By this he means that they might encourage people to behave better as members of society. 21 Answer: NOT GIVEN Note Paragraph B: The writer talks about different opinions of various stadiums, saying that what people think of some stadiums is connected more with the events that happen there than with the building itself, and also saying that some stadiums are rather poorly designed’. However, he does not compare any stadiums in terms of the amount of criticism they have received. 22 Answer: FALSE Note Paragraph C: ‘Nor, as a spectator The writer says that ‘the bloated Games programme’ places certain demands on stadium designers. He means that designers are forced to produce certain designs because of the large number of events that have to be staged in the Olympics. They are therefore not free to choose what they might consider to be good designs, and so it is not their fault that the designs have not been better. Questions 23-26 23 Answer: natural lighting Note ‘In order to reduce … '. The design made it possible to use this ‘in as many public areas as possible’. 24 Answer: mechanical air-conditioning Note ‘Wherever possible … ‘. 25 Answer: storm water Note This ran off the roof and into storage tanks and was then used in toilets. 26 Answer: pitch irrigation Note This was collected separately from storm water, ran off the roof and into storage tanks, and was then used on the playing area. READING Passage 3 Questions 27-29 27, 28, 29 Answer: C/D/E (in any order) Note Option C: 1st paragraph.’I say “attempted" …’. The writer refers to the ‘absence of community’, which means that the people could not be considered a single group with much in common. They were all different from each other and lived separate lives. Option D: 1st paragraph, same sentence. The writer refers to the ‘intensely private nature of London households’, which means that people did not want to give private information on their personal lives. Option E: 3rd paragraph, 1 sentence. The writer says that he has had to ‘gloss over’ the fact that (avoid drawing attention to the unfortunate fact that) the amount of his involvement differed greatly with different households. Some he only talked to about their shopping, and some he visited at home and accompanied when they went shopping. He would clearly have preferred to have the maximum involvement with all the households, but he was not able to do so. Option A is not a possible answer. 1st and 2nd paragraphs; He says that he aimed to carry out an ethnography (a kind of study) of shopping in a certain place and that his part would focus on ‘shopping itself’. He does not say that he was ever not sure what the study should be about. Option B is not a possible answer. 1st paragraph: He found 76 households, but he does not say what number he tried to find. He was not able to get very involved with some of them, but he does not say he found it hard to get enough people willing to take part in his study. Option F is not a possible answer. 3rd paragraph: He was more involved with some people than with others, but he does not say that some people agreed to take part and then changed their minds. Questions 30-37 30 Answer: NOT GIVEN Note 4th paragraph: The writer describes both traditions and says that he intends to ’emphasize the latter’ (anthropological generalisation), but he does not say whether one Is more generally used than the other. 31 Answer: YES Note 4th paragraph, last part: The writer says that he intends to use anthropological generalisation because almost all of the acts of shopping in his study ‘exhibit a normative form’. This is clearly something which he feels makes anthropological generalisation appropriate. 32 Answer: YES Note 4 thparagraph, last sentence: He says that he believes that the ‘heterogenous’ (consisting of many different kinds of people) group he studied carried out ‘homogenous cultural practices’ (ones that are all of the same type). He is therefore saying that he can generalise about shopping because the people he studied all did the same things. 33 Answer: NO Note 5th paragraph, 1st sentence: The writer says that his ideas are ‘at odds with’ (opposed to) ‘most of the literature on this topic’. His conclusions will therefore not agree with those of other research. 34 Answer: YES Note 5th paragraph: ‘My premise … shopper’. The writer is saying that the basis of his theory is that people usually don’t do shopping for their own benefit but for other reasons. 35 Answer: NOT GIVEN Note 5th paragraph, second half: The writer gives two purposes he believes shopping to have and analyses in both cases the motives of people when they are shopping. However, he does not say whether or not he thinks people analyse their own motives when they are shopping – the analysis is his. 36 Answer: NO Note 5th paragraph, last sentence: The writer says That shopping ‘transcends any immediate utility’ (its aim is higher than simply the practical use of the things that are bought). He is saying that shopping is concerned with general values in life more than with the actual things people buy. 37 Answer: NO Note Last paragraph, 1st sentence: The writer says that he never thought while he was carrying out his study that the subject of sacrifice would come into it. However, that subject did come into it later. His study was not an attempt lo test the theories he now has; the theories, which include the area of ‘sacrifice’, developed after he had done the study. He therefore did not know before he started the study what theories would result from it. Questions 38—40 38 Answer: thrift Note The literature … chapter 3′. He says that he first thought that the research most closely connected with his own research in London was research on thrift (being careful with money). 39 Answer: Hubert and Mauss Note The crucial element… my interpretation’. He says that work done by Bataille led him to the area of sacrifice, but that the work done by Hubert and Mauss is ‘the primary grounds for my interpretation’. His interpretation is mainly based on their work. 40 Answer: colloquial/metaphorical Note He says that he uses the colloquial sense of the word ‘only rarely’, and that the metaphorical sense may be useful at some point, but it is ‘secondary’ {of less importance) in comparison with the sense of the word in connection with ‘structure’ (here he means in connection with ‘ancient’ or ‘traditional’ sacrifice’). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

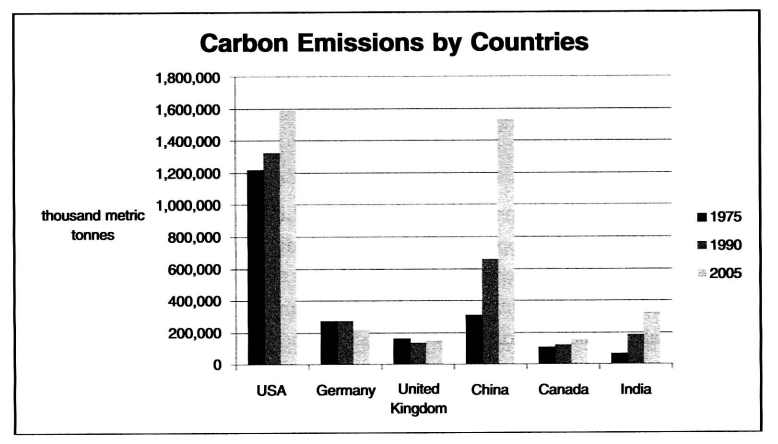

| IELTS Writing Practice Test 33 (Task 1 & 2) & Sample Answers Posted: 07 Jan 2017 10:15 PM PST IELTS Writing Topic:WRITING TASK 1 You should spend about 20 minutes on this task. The bar graph below shows the amount of carbon emissions in different countries during three different years. Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant. Write at least 150 words. WRITING TASK 2 You should spend about 40 minutes on this task. Write about the following topic: A number of tertiary courses require students to undertake a period of unpaid work at art institution or organisation as part of their programme. What are the advantages and disadvantages of thừ type of course requữement? Give reasons for your answer and include any relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience. Write at least 250 words.

SAMPLE ANSWERSTask 1 Model Answer The bar graph illustrates the quantity of carbon emissions produced by six countries in 1975,1990, and 2005. The USA emitted the largest amount of carbon for all three years, showing an increase from slightly over 1,200,000 thousand metric tonnes in 1975 to just under 1,600,000 thousand mctric tonnes in 2005. China's level of carbon emissions more than doubled from 300.000 thousand metric tonnes in 1975 to over 600,000 thousand metric tonnes in 1990 before more than doubling again to approximately 1.6 million thousand metric tonnes in 2005. In contrast, Germany's carbon emissions reduced slightly from approximately 250,000 in 1975 and 1990 to roughly 200,000 in 2005. The only other country to reduce emissions was the United Kingdom between 1975 (approximately 180,000) and 1990 (about 160,000), although this was quite slight and rose again in 2005 to 170,000. Canada's level increased slightly each year to match the UK in 2005, and carbon emissions in India jumped from approximately 80.000 in 1975 to 350,000 in 2005. On the whole, the two largest contributors to carbon emissions were the USA and China. (181 words) Task 2 Model Answer As part of a varied and stimulating curriculum, many universities and tertiary providers often offer student internships with companies or other organisations as a component of study. This trend has both benefits and drawbacks. One of the mam advantages is that an internship in an appropriate place ofTers students the chance to integrate their theory and knowledge in a real-life, practical setting. The example of student doctors and nurses illustrates the value of practical internships: how else would students learn to practise medicine but in an authentic, supervised context? In addition, internships and practicum placements can often lead to a job opportunity for the student upon graduating, or at the very least, a good set of contacts for the commencement of their professional life. In terms of assessment it also gives the university a clear picture of how the student is progressing against industry standards, and whether the course is meeting the needs of that particular industry. However, there are several disadvantages to these types of placements. First of all, universities can sometimes have difficulty in securing good quality, suitable placements for their students or, even worse, students are left to their own devices to arrange a placement. This is unsatisfactory and puts students at a disadvantage. As well as this, sometimes students in these types of placements get used to doing menial task which are well beneath their capabilities, simply because they are perceived as inexperienced and incapable. To conclude, student placements arc an excellent way to provide practical experience and support our future professionals to gain the skills they need to succeed, but these placements must be monitored and facilitated carefully. (273 words) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two-Word Prepositions to Score Band 7.0+ in IELTS Writing & Speaking (Part 3) Posted: 07 Jan 2017 10:14 PM PST Let’s gear yourself up for the IELTS Writing & Speaking with "academic" prepositions that are not so frequently used but suitable for academic writing and speaking. Learning these prepositions and making use of them in IELTS writing & speaking will help you boost your IELTS score as well as contributing to your academic pursuit.According to

Example: You have been absent six times according to our records.

Example: The salary will be fixed according to qualifications and experience. Ahead of

Example: Ahead of us lay ten days of intensive training.

Example: I finished several days ahead of the deadline.

Example: She was always well ahead of the rest of the class. Apart from/Aside from See Except As for Alternative to Regarding Owing to Because of Example: The game was cancelled owing to torrential rain. Prior to Before something Example: during the week prior to the meeting Regardless of Paying no attention to something/somebody; treating something/somebody as not being important Example: The amount will be paid to everyone regardless of whether they have children or not. Subsequent to After, following Example: There have been further developments subsequent to our meeting. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IELTS Reading Recent Actual Test 10 in 2016 with Answer Key Posted: 07 Jan 2017 07:42 PM PST SECTION 1Dirty river but clean water Floods can occur in rivers when the flow rate exceeds the capacity of the river channel, particularly at bends or meanders in the waterway. Floods often cause damage to homes and businesses if they are in the natural flood plains of rivers. While riverine flood damage can be eliminated by moving away from rivers and other bodies of water, people have traditionally lived and worked by rivers because the land is usually flat and fertile and because rivers provide easy travel and access to commerce and industry. A FIRE and flood are two of humanity's worst nightmares. People have, therefore, always sought to control them. Forest fires are snuffed out quickly. The flow of rivers is regulated by weirs and dams. At least,that is how it used to be. But foresters have learned that forests need fires to clear out the brush and even to get seeds to germinate. And a similar revelation is now dawning on hydrologists. Rivers 一 and the ecosystems they support — need floods. That is why a man-made torrent has been surging down the Grand Canyon. By Thursday March 6th it was running at full throttle, which was expected to be sustained for 60 hours. B Floods once raged through the canyon every year. Spring Snow from as far away as Wyoming would melt and swell the Colorado river to a flow that averaged around 1,500 cubic metres (50,000 cubic feet) a second. Every eight years or so, that figure rose to almost 3,000 cubic metres. These floods infused the river with sediment, carved its beaches and built its sandbars. C However, in the four decades since the building of the Glen Canyon dam, just upstream of the Grand Canyon, the only sediment that it has collected has come from tiny, undammed tributaries. Even that has not been much use as those tributaries are not powerful enough to distribute the sediment in an ecologically valuable way. D This lack of flooding has harmed local wildlife. The humpback chub, for example, thrived in the rust-red waters of the Colorado. Recently, though, its population has crashed. At first sight, it looked as if the reason was that the chub were being eaten by trout introduced for sport fishing in the mid-20th century. But trout and chub co-existed until the Glen Canyon dam was built, so something else is going on. Steve Gloss, of the United States' Geological Survey (USGS), reckons that the chub's decline is the result of their losing their most valuable natural defense, the Colorado's rusty sediment. The chub were well adapted to the poor visibility created by the thick, red water which gave the river its name, and depended on it to hide from predators. Without the cloudy water the chub became vulnerable. E And the chub are not alone. In the years since the Glen Canyon dam was built, several species have vanished altogether. These include the Colorado pike-minnow, the razorback sucker and the roundtail chub. Meanwhile, aliens including fathead minnows, channel catfish and common carp, which would have been hard, put to survive in the savage waters of the undammed canyon, have moved in. F So flooding is the obvious answer. Unfortunately, it is easier said than done. Floods were sent down the Grand Canyon in 1996 and 2004 and the results were mixed. In 1996 the flood was allowed to go on too long. To start with, all seemed well. The floodwaters built up sandbanks and infused the river with sediment. Eventually, however, the continued flow washed most of the sediment out of the canyon. This problem was avoided in 2004,but unfortunately, on that occasion, the volume of sand available behind the dam was too low to rebuild the sandbanks. This time, the USGS is convinced that things will be better. The amount of sediment available is three times greater than it was in 2004. So if a flood is going to do some good, this is the time to unleash one. G Even so, it may turn out to be an empty gesture. At less than 1,200 cubic metres a second, this flood is smaller than even an average spring flood, let alone one of the mightier deluges of the past. Those glorious inundations moved massive quantities of sediment through the Grand Canyon, wiping the slate dirty, and making a muddy mess of silt and muck that would make modem river rafters cringe. Questions 1-7 Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 1-7 on your answer sheet, write

1. Damage caused by fire is worse than that caused by flood. 2. The flood peaks at almost 1500 cubic meters every eight years. 3. Contribution of sediments delivered by tributaries has little impact. 4. Decreasing number of chubs is always caused by introducing of trout since mid-20th 5. It seemed that the artificial flood in 1996 had achieved success partly at the very beginning 6. In fact, the yield of artificial flood water is smaller than an average natural flood at present. 7. Mighty floods drove fast moving flows with clean and high quality water. Questions 8-13 Complete the summary below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 8-13 on your answer sheet. The Eco- Impact of the Canyon Dam Floods are peopled nightmare. In the past, canyon was raged by flood every year. The snow from far Wyoming would melt in the season of 8………………. and caused a flood flow peak in Colorado river. In the four decades after people built the Glen Canyon dam, it only could gather 9…………………………………. together from tiny, undammed tributaries. humpback chub population reduced, why? Then, several species disappeared including Colorado pike-minnow, 10 ………………… and the round-tail chub. Meanwhile, some moved in such as fathead minnows, channel catfish and 11………………………………The non-stopped flow leaded to the washing away of the sediment out of the canyon, which poses great threat to the chubs because it has poor 12……………………… away from predators. In addition, the volume of 13…………………… available behind the dam was too tow to rebuild the bars and flooding became more serious. SECTION 2Smell and Memory SMELLS LIKE YESTERDAY Why does the scent of a fragrance or the mustiness of an old trunk trigger such powerful memories of childhood? New research has the answer, writes Alexandra Witze. A You probably pay more attention to a newspaper with your eyes than with your nose. But lift the paper to your nostrils and inhale. The smell of newsprint might carry you back to your childhood, when your parents perused the paper on Sunday mornings. Or maybe some other smell takes you back- the scent of your mother’s perfume, the pungency of a driftwood campfire. Specific odours can spark a flood of reminiscences. Psychologists call it the “Proustian phenomenon ",after French novelist Marcel Proust. Near the beginning of the masterpiece In Search of Lost Time, Proust's narrator dunks a madeleine cookie into a cup of tea – and the scent and taste unleash a torrent of childhood memories for 3000 pages. B Now, this phenomenon is getting the scientific treatment. Neuroscientists Rachel Herz, a cognitive neuroscientist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, have discovered, for instance, how sensory memories are shared across the brain, with different brain regions remembering the sights, smells, tastes and sounds of a particular experience. Meanwhile, psychologists have demonstrated that memories triggered by smells can be more emotional, as well as more detailed, than memories not related to smells. When you inhale, odour molecules set brain cells dancing within a region known as the amygdala,a part of the brain that helps control emotion. In contrast, the other senses, such as taste or touch, get routed through other parts of the brain before reaching the amygdala. The direct link between odours and the amygdala may help explain the emotional potency of smells. “There is this unique connection between the sense of smell and the part of the brain that processes emotion,” says Rachel Herz. C But the links don't stop there. Like an octopus reaching its tentacles outward, the memory of smells affects other brain regions as well. In recent experiments, neuroscientists at University College London (UCL) asked 15 volunteers to look at pictures while smelling unrelated odours. For instance, the subjects might see a photo of a duck paired with the scent of a rose, and then be asked to create a story linking the two. Brain scans taken at the time revealed that the volunteers' brains were particularly active in a region known as the olfactory cortex, which is known to be involved in processing smells. Five minutes later, the volunteers were shown the duck photo again, but without the rose smell. And in their brains, the olfactory cortex lit up again, the scientists reported recently. The fact that the olfactory cortex became active in the absence of the odour suggests that people's sensory memory of events is spread across different brain regions. Imagine going on a seaside holiday, says UCL team leader, Jay Gottfried. The sight of the waves becomes stored in one area, whereas the crash of the surf goes elsewhere, and the smell of seaweed in yet another place. There could be advantages to having memories spread around the brain. “You can reawaken that memory from any one of the sensory triggers,” says Gottfried. ''Maybe the smell of the sun lotion, or a particular sound from that day, or the sight of a rock formation.” Or – in the case of an early hunter and gatherer ( out on a plain – the sight of a lion might be trigger the urge to flee, rather than having to wait for the sound of its roar and the stench of its hide to kick in as well. D Remembered smells may also carry extra emotional baggage, says Herz. Her research suggests that memories triggered by odours are more emotional than memories triggered by other cues. In one recent study, Herz recruited five volunteers who had vivid memories associated with a particular perfume, such as opium for Women and Juniper Breeze from Bath and Body Works. She took images of the volunteers' brains as they sniffed that perfume and an unrelated perfume without knowing which was which. (They were also shown photos of each perfume bottle.) Smelling the specified perfume activated the volunteers brains the most,particularly in the amygdala, and in a region called the hippocampus,which helps in memory formation. Herz published the work earlier this year in the journal Neuropsychologia. E But she couldn’t be sure that the other senses wouldn’t also elicit a strong response. So in another study Herz compared smells with sounds and pictures. She had 70 people describe an emotional memory involving three items – popcorn, fresh-cut grass and a campfire. Then they compared the items through sights,sounds and smells. For instance, the person might see a picture of a lawnmower, then sniff the scent of grass and finally listen to the lawnmower's sound. Memories triggered by smell were more evocative than memories triggered by either sights or sounds. F Odour-evoked memories may be not only more emotional, but more detailed as well. Working with colleague John Downes,psychologist Simon Chu of the University of Liverpool started researching odour and memory partly because of his grandmother’s stories about Chinese culture. As generations gathered to share oral histories, they would pass a small pot of spice or incense around; later, when they wanted to remember the story in as much detail as possible, they would pass the same smell around again. “It's kind of fits with a lot of anecdotal evidence on how smells can be really good reminders of past experiences,” Chu says. And scientific research seems to bear out the anecdotes. In one experiment, Chu and Downes asked 42 volunteers to tell a life story, then tested to see whether odours such as coffee and cinnamon could help them remember more detail in the story. They could. G Despite such studies, not everyone is convinced that Proust can be scientifically analysed. In the June issue of Chemical Senses, Chu and Downes exchanged critiques with renowned perfumer and chemist J. Stephan Jellinek. Jellinek chided the Liverpool researchers for, among other things, presenting the smells and asking the volunteers to think of memories, rather than seeing what memories were spontaneously evoked by the odours. But there’s only so much science can do to test a phenomenon that's inherently different for each person, Chu says. Meanwhile, Jellinek has also been collecting anecdotal accounts of Proustian experiences, hoping to find some there is a case to be made that surprise may be a major aspect of the Proust phenomenon,” he says. “That's why people are so struck by these memories" No one knows whether Proust ever experienced such a transcendental moment. But his notions of memory, written as fiction nearly a century ago, continue to inspire scientists of today. Questions 14-18 Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-C) with opinions or deeds below. Write the appropriate letters A- C in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet. NB you may use any letter more than once A Rachel Herz B Simon Chu C Jay Gottfried 14. Found pattern of different sensory memories stored in various zones of a brain. 15. Smell brings detailed event under a smell of certain substance. 16. Connection of smell and certain zones of brain is different with that of other senses. 17. Diverse locations of stored information help us keep away the hazard. 18. There is no necessary correlation between smell and processing zone of brain. Questions 19-22 Choose the correct letter, A, B,C or D. Write your answers in boxes 19-22 on your answer sheet. 19. What does the experiment conducted by Herz show? A Women are more easily addicted to opium medicine B Smell is superior to other senses in connection to the brain C Smell is more important than other senses D Amygdala is part of brain that stores processes memory 20. What does the second experiment conducted by Herz suggest? A Result directly conflicts with the first one B Result of her first experiment is correct C Sights and sounds trigger memories at an equal level D Lawnmower is a perfect example in the experiment 21. What is the outcome of experiment conducted by Chu and Downes? A smell is the only functional under Chinese tradition B half of volunteers told detailed stories C smells of certain odours assist story tellers D odours of cinnamon is stronger than that of coffee 22. What is the comment of Jellinek to Chu and Downers in the issue of Chemical Senses: A Jellinek accused their experiment of being unscientific B Jellinek thought Liverpool is not a suitable place for experiment C Jellinek suggested that there was no further clue of what specific memories aroused D Jellinek stated that experiment could be remedied Questions 23-26 Summary Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet. In the experiments conducted by UCL, participants were asked to look at a picture with a scent of a flower, then in the next stage, everyone would have to……………………… 23………….. for a connection. A method called……………… 24…………. suggested that specific area of brain named……………. 25…………. were quite active. Then in an another paralleled experiment about Chinese elders, storytellers could recall detailed anecdotes when smelling bowl of…………… 26……………… or incense around. SECTION 3Soviet's new working week Historian investigates how Stalin changed the calendar to keep the Soviet people continually at work. A "There are no fortresses that Bolsheviks cannot storm". With these words, Stalin expressed the dynamic self-confidence of the Soviet Union's Five Year Plan: weak and backward Russia was to turn overnight into a powerful modem industrial country. Between 1928 and 1932,production of coal, iron and steel increased at a fantastic rate, and new industrial cities sprang up, along with the world's biggest dam. Everyone's life was affected, as collectivised farming drove millions from the land to swell the industrial proletariat. Private enterprise disappeared in city and country, leaving the State supreme under the dictatorship of Stalin. Unlimited enthusiasm was the mood of the day, with the Communists believing that iron will and hard-working manpower alone would bring about a new world. B Enthusiasm spread to time itself, in the desire to make the state a huge efficient machine, where not a moment would be wasted, especially in the workplace. Lenin had already been intrigued by the ideas of the American Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), whose time-motion studies had discovered ways of stream-lining effort so that every worker could produce the maximum. The Bolsheviks were also great admirers of Henry Ford's assembly line mass production and of his Fordson tractors that were imported by the thousands. The engineers who came with them to train their users helped spread what became a real cult of Ford. Emulating and surpassing such capitalist models formed part of the training of the new Soviet Man, a heroic figure whose unlimited capacity for work would benefit everyone in the dynamic new society. All this culminated in the Plan, which has been characterized as the triumph of the machine, where workers would become supremely efficient robot-like creatures. C Yet this was Communism whose goals had always included improving the lives of the proletariat. One major step in that direction was the sudden announcement in 1927 that reduced the working day from eight to seven hours. In January 1929, all Indus-tries were ordered to adopt the shorter day by the end of the Plan. Workers were also to have an extra hour off on the eve of Sundays and holidays. Typically though, the state took away more than it gave, for this was part of a scheme to increase production by establishing a three-shift system. This meant that the factories were open day and night and that many had to work at highly undesirable hours. D Hardly had that policy been announced, though, than Yuri Larin, who had been a close associate of Lenin and architect of his radical economic policy, came up with an idea for even greater efficiency. Workers were free and plants were closed on Sundays. Why not abolish that wasted day by instituting a continuous work week so that the machines could operate to their full capacity every day of the week? When Larin presented his idea to the Congress of Soviets in May 1929, no one paid much attention. Soon after, though, he got the ear of Stalin, who approved. Suddenly, in June, the Soviet press was filled with articles praising the new scheme. In August, the Council of Peoples' Commissars ordered that the continuous work week be brought into immediate effect, during the height of enthusiasm for the Plan, whose goals the new schedule seemed guaranteed to forward. E The idea seemed simple enough, but turned out to be very complicated in practice. Obviously, the workers couldn't be made to work seven days a week, nor should their total work hours be increased. The Solution was ingenious: a new five-day week would have the workers on the job for four days, with the fifth day free; holidays would be reduced from ten to five, and the extra hour off on the eve of rest days would be abolished. Staggering the rest-days between groups of workers meant that each worker would spend the same number of hours on the job, but the factories would be working a full 360 days a year instead of 300. The 360 divided neatly into 72 five-day weeks. Workers in each establishment (at first factories,then stores and offices) were divided into five groups, each assigned a colour which appeared on the new Uninterrupted Work Week calendars distributed all over the country. Colour-coding was a valuable mnemonic device, since workers might have trouble remembering what their day off was going to be, for it would change every week. A glance at the colour on the calendar would reveal the free day, and allow workers to plan their activities. This system, however, did not apply to construction or seasonal occupations, which followed a six-day week, or to factories or mines which had to close regularly for maintenance: they also had a six-day week, whether interrupted (with the same day off for everyone) or continuous. In all cases, though, Sunday was treated like any other day. F Official propaganda touted the material and cultural benefits of the new scheme. Workers would get more rest; production and employment would increase (for more workers would be needed to keep the factories running continuously); the standard of living would improve. Leisure time would be more rationally employed, for cultural activities (theatre, clubs, sports) would no longer have to be crammed into a weekend, but could flourish every day, with their facilities far less crowded. Shopping would be easier for the same reasons. Ignorance and superstition, as represented by organized religion, would suffer a mortal blow, since 80 per cent of the workers would be on the job on any given Sunday. The only objection concerned the family, where normally more than one member was working: well, the Soviets insisted, the narrow family was far less important than the vast common good and besides, arrangements could be made for husband and wife to share a common schedule. In fact, the regime had long wanted to weaken or sideline the two greatest potential threats to its total dominance: organised religion and the nuclear family. Religion succumbed, but the family, as even Stalin finally had to admit, proved much more resistant. G The continuous work week, hailed as a Utopia where time itself was conquered and the sluggish Sunday abolished forever, spread like an epidemic. According to official figures, 63 per cent of industrial workers were so employed by April 1930; in June, all industry was ordered to convert during the next year. The fad reached its peak in October when it affected 73 per cent of workers. In fact, many managers simply claimed that their factories had gone over to the new week, without actually applying it. Conforming to the demands of the Plan was important; practical matters could wait. By then, though, problems were becoming obvious. Most serious (though never officially admitted), the workers hated it. Coordination of family schedules was virtually impossible and usually ignored, so husbands and wives only saw each other before or after work; rest days were empty without any loved ones to share them 一 even friends were likely to be on a different schedule. Confusion reigned: the new plan was introduced haphazardly, with some factories operating five-, six- and seven-day weeks at the same time, and the workers often not getting their rest days at all. H The Soviet government might have ignored all that (It didn't depend on public approval) ,but the new week was far from having the vaunted effect on production. With the complicated rotation system, the work teams necessarily found themselves doing different kinds of work in successive weeks. Machines, no longer consistently in the hands of people who knew how to tend them, were often poorly maintained or even broken. Workers lost a sense of responsibility for the special tasks they had normally performed. I As a result, the new week started to lose ground. Stalin’s speech of June 1931, which criticised the "depersonalised labor" its too hasty application had brought, marked the beginning of the end. In November, the government ordered the widespread adoption of the six-day week, which had its own calendar, with regular breaks on the 6th, 12th, 18th,24th, and 30th,with Sunday usually as a working day. By July 1935, only 26 per cent of workers still followed the continuous schedule, and the six-day week was soon on its way out. Finally, in 1940,as part of the general reversion to more traditional methods, both the continuous five-day week and the novel six-day week were abandoned, and Sunday returned as the universal day of rest. A bold but typically ill-conceived experiment was at an end. Questions 27-34 Reading Passage 2 has nine paragraphs A-I. Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below. Write the correct number i-xii in boxes 27-34 on your answer sheet.

27. Paragraph A 28. Paragraph D 29. Paragraph E 30. Paragraph F 31. Paragraph G 32. Paragraph H 33. Paragraph I Example Answer Paragraph C iii Questions 35-37 Choose the correct letter A,B,C or D. Write your answers in boxes 35-37 on your answer sheet. 35. According to paragraph A, Soviet's five year plan was a success because A Bolsheviks built a strong fortress. B Russia was weak and backward. C industrial production increased. D Stalin was confident about Soviet's potential. 36. Daily working hours were cut from eight to seven to A improve the lives of all people. B boost industrial productivity. C get rid of undesirable work hours. D change the already establish three-shift work system. 37. Many factory managers claimed to have complied with the demands of the new work week because A they were pressurized by the state to do so. B they believed there would not be any practical problems. C they were able to apply it. D workers hated the new plan. Questions 38-40 Answer the questions below using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet. 38. Whose idea of continuous work week did Stalin approve and helped to implement? 39. What method was used to help workers to remember the rotation of their off days? 40. What was the most resistant force to the new work week scheme? ANSWER KEYS

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| You are subscribed to email updates from IELTS Materials and Resources, Get IELTS Tips, Tricks & Practice Test. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment